“I Just Wanna Stop” legend Gino Vannelli about to offer Arcada Theatre five distinctive decades

Photo provided by Arcada Theatre

Photo provided by Arcada Theatre

One of the most distinctive singer/songwriters of the 1970s and ‘80s became even more versatile from the ‘90s through now, but not before stepping out of the limelight at the peak of gold and platinum sales to go to college for a full course load of some pretty serious studies.

Along the way, Canada’s Gino Vannelli scored soulful singles such as “I Just Wanna Stop,” “Living Inside Myself,” “People Gotta Move” and “Hurts To Be in Love,” while changing lanes completely come the “Canto” collection, amongst many other endeavors, even performing at the Vatican at the personal request of Pope John Paul II.

Nowadays, he’s arguably more active than ever, recording nearly every year, including the upcoming “The Life I Got,” plus making up for lost time on the road with five decades’ worth of material to revisit.

Vannelli rang Chicago Concert Reviews in advance of an Arcada Theatre appearance on Thursday, September 21 for a glimpse into building a grassroots fan base from scratch (and perhaps a little help from Stevie Wonder) long before the internet, why superstardom was so unsettling and how the 71-year-old currently takes care of such a priceless voice.

What do you recall about any previous performances in the Chicago area?

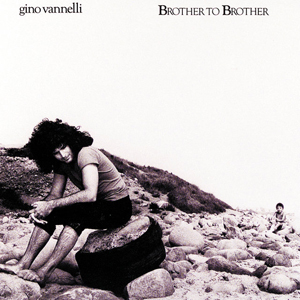

Gino Vannelli: I believe we played the Arcada four or five years ago. I remember the ‘70s quite fondly. We started, I think, playing a club that used to be called Mister Kelly’s and that’s where the career really started. Actually no, it was before that, 1974, I opened up for, I think, an all-female group called Isis in some kind of theatre and it was a debacle. We released “Storm At Sunup” in 1975. We started getting some jazz fusion play in Chicago, and next thing you know, I’m at Mister Kelly’s and we sold out the whole week. Then we started playing other places, like Symphony [Center] and the Arie Crown Theater. Then we ended up in 1979, after the “Brother To Brother” record, playing the Chicago Stadium and then we didn’t tour for 12 years after that.

Gino Vannelli: I believe we played the Arcada four or five years ago. I remember the ‘70s quite fondly. We started, I think, playing a club that used to be called Mister Kelly’s and that’s where the career really started. Actually no, it was before that, 1974, I opened up for, I think, an all-female group called Isis in some kind of theatre and it was a debacle. We released “Storm At Sunup” in 1975. We started getting some jazz fusion play in Chicago, and next thing you know, I’m at Mister Kelly’s and we sold out the whole week. Then we started playing other places, like Symphony [Center] and the Arie Crown Theater. Then we ended up in 1979, after the “Brother To Brother” record, playing the Chicago Stadium and then we didn’t tour for 12 years after that.

What’s on deck for this show you have coming to the Arcada?

Vannelli: I go back all the way to 1974 with the material. We have a rhythm section, five guys in the band and three horns. We go all the way back to the early ‘70s, and of course, there’s modifications here and there to the arrangements. In some cases, the songs are 50-years-old and I pick the ones that are still a little bit difficult to sing, so it kind of keeps me sharper and it’s close to a two-hour show. I mean, the only reason why I still tour is because there’s still a mountain to climb.

How do you keep your voice in shape to be able to tackle these complicated songs?

Vannelli: There’s a strong element of discipline to it all, from daily disciplines of diet, exercise and your sleep hours because it has a way of building up or building down. Then singing a lot, but not too much, when I prepare for going out on the road. I have a sort of regiment that I approach, which is sing a quarter of a show, then two days later, half the show, then two days later, three quarters of the show, and then by the time I get to the show, my voice is totally acclimated to these 16 songs.

Could you give us a little background about getting started in the jazz realm before becoming a star on your own and what you learned from some of the people you supported?

Vannelli: I never really supported anybody other than being the 10-year-old drummer in a club in Montreal that was a support group or a release band basically, but that for me was [when] the education really started because seeing certain artists live, like Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, they really instilled in me a very high watermark. When you’re seated in this small 400-seat place and you hear those kind of instruments and that kind of musicianship at a very young age, it made a very strong imprint, so I always tried to climb my way up to that watermark and that was the first time.

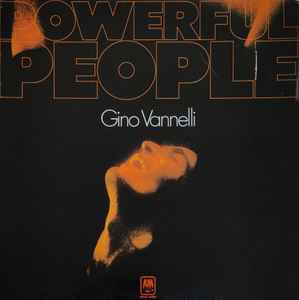

Then later on, I got to tour with Stevie Wonder. That was a successful tour for me in 1974. I played eight cities. Stevie was very gracious for inviting me. Chaka Khan happened to be sick. We met by serendipity. He liked my first album and asked me to tour with him. I did, I think, open up for Gladys Knight once. I tried opening up for Steppenwolf, I think, once. They were all pretty much disastrous (laughs), so that’s when I decided, “I’m going to do it another way.” All the managers and agents wanted me to play in front of a large audience after “People Gotta Move” was a Top Ten R&B hit, so I decided to go another way. “I’m going to go the small club way and build my own audience.” And that’s how I started building my own audience in late ’74, ’75, ’76, and low and behold, two years later we’re playing concert halls, without really having a Top 40 single after “People Gotta Move” until “I Just Wanna Stop.” I remember when we played Chicago, we played two nights at the Arie Crown in ’76 or ’77 and we didn’t have any singles. We drew ten thousand people just because, in those days, people really listened to music and music was really a priority in their lives. They listened to radio and they were into albums, and would listen to whole albums. The attention span of your average listener was a lot greater than it is today…But a lot of those people that remember those days still come to the concerts and want that same kind of thing, only they want it 20, 30, 40 years later. If I would play it exactly as it was 40 years ago, they wouldn’t remember it as fondly, so you have to kind of build up or redecorate a little bit so that they remember it exactly as they thought it was (laughs).

Then later on, I got to tour with Stevie Wonder. That was a successful tour for me in 1974. I played eight cities. Stevie was very gracious for inviting me. Chaka Khan happened to be sick. We met by serendipity. He liked my first album and asked me to tour with him. I did, I think, open up for Gladys Knight once. I tried opening up for Steppenwolf, I think, once. They were all pretty much disastrous (laughs), so that’s when I decided, “I’m going to do it another way.” All the managers and agents wanted me to play in front of a large audience after “People Gotta Move” was a Top Ten R&B hit, so I decided to go another way. “I’m going to go the small club way and build my own audience.” And that’s how I started building my own audience in late ’74, ’75, ’76, and low and behold, two years later we’re playing concert halls, without really having a Top 40 single after “People Gotta Move” until “I Just Wanna Stop.” I remember when we played Chicago, we played two nights at the Arie Crown in ’76 or ’77 and we didn’t have any singles. We drew ten thousand people just because, in those days, people really listened to music and music was really a priority in their lives. They listened to radio and they were into albums, and would listen to whole albums. The attention span of your average listener was a lot greater than it is today…But a lot of those people that remember those days still come to the concerts and want that same kind of thing, only they want it 20, 30, 40 years later. If I would play it exactly as it was 40 years ago, they wouldn’t remember it as fondly, so you have to kind of build up or redecorate a little bit so that they remember it exactly as they thought it was (laughs).

What do you feel made you so distinctive compared to what else might have been out in the ‘70s and early ‘80s?

Vannelli: It was definitely a fusion of jazz, pop, rhythm and blues, and a little Latin, but the thing about it that was a little bit unique is I was a lyricist, and also a melodist, and also a singer. [In the] early ‘70s, not that many people were doing it in that way with orchestration that my brothers and I were applying to the recordings. I suppose the reason for it was my deep appreciation for the big bands, my deep appreciation for the great singers of the ‘40s and ‘50s, my deep appreciation for R&B/soul music, gospel music, and also, my deep appreciation for the rhythm of Brazilian and South American music. Somehow, it all came together in a lot of the albums, and then it of course evolved into other things. In some cases, a little more Americana. In some cases, a little more folky with jazz. In some cases, a little bit more soulful jazz. I mean it kind of moves a little bit, but really, it’s an appreciation for all those styles that came naturally to me. It’s not that I consciously said to myself, “I’m going to take this, and take that, and put in a stew, and make a new soup out of it.” It’s just that I had listened to all those things all my life, since I was six or seven, and I think another one I could throw in there is classical or opera that I knew a lot about by the time I was ten. I had a great appreciation of it, so it’s somewhere inside the recordings. There’s a touch of that too.

What was it like for you surrounding the landmark period of “Brother To Brother” and “I Just Wanna Stop”?

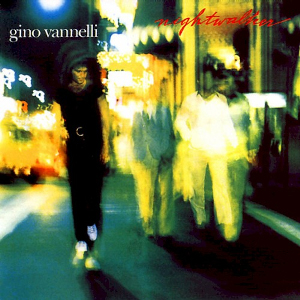

Vannelli: I think the word is “whirlwind.” It just kind of sweeps you off your feet for a second. I was really one of those kind of guys that didn’t really want to get swept off my feet. I was already writing “Nightwalker” and “Living Inside Myself,” and being busy planning the next record. I look back upon it and I could’ve enjoyed it a little bit more, but I was already planning for the next. In those days, I didn’t really take too much time to enjoy any success I had. It was all business and not much play. And that’s why I, in a sense, broke down by the time I had released “Nightwalker” and we had a big hit with “Living Inside Myself.”

My career had sort of taken a turn and I decided not to tour yet keep on writing, but I decided to go back to college, study theology, literature, and eventually, humanities and experiential theology, which is really seeing what people knew, not only academically, but experientially. That was like a seven or eight year period, from like 32-years-old to 38 or 39, and it culminated in the study of the Jewish Kabbalah for a crash course to understand its basic premise and its application. After that, I had a choice whether I wanted to really get back into touring and do this earnestly instead of just write and record, so I decided to move from Los Angeles to the Northwest, built my own studio and started recording. It wasn’t exactly mainstream material. Following your heart was a little bit of a rocky road at first, but it was a road and that led to a lot more gratification then the smooth road of the road more traveled.

My career had sort of taken a turn and I decided not to tour yet keep on writing, but I decided to go back to college, study theology, literature, and eventually, humanities and experiential theology, which is really seeing what people knew, not only academically, but experientially. That was like a seven or eight year period, from like 32-years-old to 38 or 39, and it culminated in the study of the Jewish Kabbalah for a crash course to understand its basic premise and its application. After that, I had a choice whether I wanted to really get back into touring and do this earnestly instead of just write and record, so I decided to move from Los Angeles to the Northwest, built my own studio and started recording. It wasn’t exactly mainstream material. Following your heart was a little bit of a rocky road at first, but it was a road and that led to a lot more gratification then the smooth road of the road more traveled.

Why prompted you to step away at the peak of it all?

Vannelli: I think that our greatest teacher, many times, is something negative that you associate with dissatisfaction, or pain, or even complete misery, that you’re not happy about something, about your life, where it’s going, a feeling of emptiness or incompleteness. For me, music was just an expression of what I could dig up from the well, and number one, the well felt like it was growing empty, and number two, it felt like there was poison water in the well, so I had to go really beyond or deeper than the well to see what was actually feeding the well. That’s a very big study and that’s a very deep study. It’s starts with academia and then it’s more than that. Then it becomes understanding what academia is trying to say, like for instance, the difference between reading about soccer or playing soccer, or reading about the way ice cream tastes or actually tasting it. So actually getting into it so deeply that I had to play it, and taste it, and be it, that took years, and then the question becomes, “What do you want to do with that knowledge? How do you apply it?”

Once I thought I would leave show business all together and go into a life of teaching or maybe just writing. I don’t know, but I decided I would go back to music and apply what I had learned, and it was no easy application, because if you try to apply it in a parallel fashion, it’s utterly boring, it’s utterly academic, so you have to let it stew and stir in you. As it stews and stirs, it comes out in a way that’s both enlightening and entertaining, at least to my ears, and that took a little while to do. Then you continue doing it and you evolve in a different way, so by the time the ‘90s came around, I started recording differently, working with different people, with symphony orchestras, big bands like the Metropole Orchestra in the Netherlands, a 60-piece band, even doing a classical record like “Canto” and performing, at that time, for Pope John Paul II. I got to do a lot of things that were very, very interesting for me as an artist, much more so than just chasing that little, cheap, golden fleece of pop success.

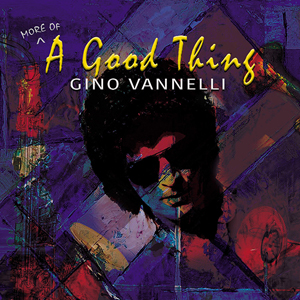

You released “Wilderness Road,” the single “How Sweet The Silence” and “(More Of) A Good Thing” in the last few years alone. What are you hoping to communicate nowadays?

Vannelli: Those are really good albums. I’m very satisfied. I just told my wife, as far as the songs are concerned on “(More Of) A Good Thing” and “Wilderness Road,” there’s hardly a word or a note I’d change, and that’s really rare for me. I just finished a brand new record. I’m working on the last song. The record’s called “The Life I Got.” You could only write this album with two conditions, that you have the years to look back on and to see with a clear perspective the last 50 years in order to be able to write about the life you have. In this case, it’s called “The Life I Got.” That’s the first condition. The second condition is to be able to have all that perspective and yet deliver it with the verve and innocence of a 20-year-old. That’s the real challenge, but those are the two conditions for this record. I made up my mind that it wasn’t good enough just to write them, that I had to be able to go in the studio and be as excited as a kid in a candy store. I wouldn’t even sing a song until I got myself into that state and we’re just about finished right now. We’re gonna start mixing in November. The record will be released on SRG/Universal in February, so I consider myself fortunate in that way that I still have major releases with the records that I’m recording, and I’m still enjoying the writing, singing and producing process.

Vannelli: Those are really good albums. I’m very satisfied. I just told my wife, as far as the songs are concerned on “(More Of) A Good Thing” and “Wilderness Road,” there’s hardly a word or a note I’d change, and that’s really rare for me. I just finished a brand new record. I’m working on the last song. The record’s called “The Life I Got.” You could only write this album with two conditions, that you have the years to look back on and to see with a clear perspective the last 50 years in order to be able to write about the life you have. In this case, it’s called “The Life I Got.” That’s the first condition. The second condition is to be able to have all that perspective and yet deliver it with the verve and innocence of a 20-year-old. That’s the real challenge, but those are the two conditions for this record. I made up my mind that it wasn’t good enough just to write them, that I had to be able to go in the studio and be as excited as a kid in a candy store. I wouldn’t even sing a song until I got myself into that state and we’re just about finished right now. We’re gonna start mixing in November. The record will be released on SRG/Universal in February, so I consider myself fortunate in that way that I still have major releases with the records that I’m recording, and I’m still enjoying the writing, singing and producing process.

It seems like you’re really making up for the lost time when your career was on hold.

Vannelli: Yeah, I mean, you’re either in the right state of mind and the right place to write, record, release and back up a record, or you’re not. It’s a terrific effort to sit down for hours, and hours, and hours, staring at one line and saying, “What’s wrong with this line?” You kind of scrape the walls of your mind, so I’ve been on this record now for almost a year and it took a phenomenal amount of energy, but it’s as good as anything I’ve done. In some cases, I’ve reached a peak that I think I only could have reached at this age, which I couldn’t do at 25 or so. [There was] no way to have the knowledge. The real catch of it is you do have the energy, and the verve, and the pizazz, and the desire to get it done when you’re 25 or even 35, but by the time you get to 70, you can have all the desire you want, but if you don’t possess the skill, the energy, and in my case, the voice, the texture and the staying power to stay ten hours a day in the studio to complete it, it can’t be done. So I consider myself very blessed, very fortunate to still have that and to be able to get it done.

Gino Vannelli performs at the Arcada Theatre on Thursday, September 21. For additional details, visit GinoV.com and ArcadaLive.com.