Kansas at 50 face and embrace “Another Fork In The Road” while eying the Chicago Theatre

Photos of violinist Joe Deninzon provided by Joel Barrios / other Kansas photos provided by Chipster PR

Photos of violinist Joe Deninzon provided by Joel Barrios / other Kansas photos provided by Chipster PR

“Carry On Wayward Son,” “Dust In The Wind,” “Point Of Know Return,” “Play The Game Tonight” and “Fight Fire With Fire” are just a few of the anthems or ballads that propelled the classic/symphonic/progressive rock band Kansas to maintain a global presence for precisely half a century.

In fact, the group currently comprised of co-founders Rich Williams (guitar) and Phil Ehart (drums), alongside Illinois’ own singer Ronnie Platt, bassist Billy Greer, keyboardist Tom Brislin and violin player Joe Deninzon is about to face and embrace “Another Fork In The Road,” thanks to a compilation and complimenting tour that stops by the Chicago Theatre on Saturday, July 15 on a run of 50 total cities to represent as many years.

Chicago Concert Reviews dialed Williams to hear about as many twists and turns as a half-hour would allow, from the early recording sessions with breaks spent shooting hoops with hookers, to headlining Madison Square Garden during an unstoppable stretch of selling over 30 million albums, to falling out of fashion for a season and finally watching it all come back around for this much-deserved milestone.

What was it like at the very beginning just as the group was getting off the ground?

Rich Williams: I never played in a band with [late violinist/vocalist] Robby Steinhardt before or [original lead singer] Steve Walsh. Well, I had started to play with Steve and then [guitarist/keyboardist] Kerry [Livgren] joined. “Can I Tell You” had been written and got us a record deal, but adding Kerry to the mix, he had so many songs already written, so we started to work on those, and twist ‘em, and turn ‘em, and it was just a very exciting time. For me and I’m sure for everyone else, I’ve never been in a band like this before. This is really something unique and special. From the first listen, I could tell that something was different about this bunch of guys. So we started working on material, and we headed into the studio and started recording. Our biggest dream was to actually record an album. That was the big time, to actually get with a record label, make an album and maybe get to tour it a little bit. We never dreamed anything beyond that…We had to wait quite a while for it because record companies have their slots when they’re releasing material. Hence, we kind of set up our own tour. We toured all over Kansas, played in all sorts of cities booking ourselves into different venues. Finally, the [“Kansas”] album came out and we were starting to get put on to some tours.

Rich Williams: I never played in a band with [late violinist/vocalist] Robby Steinhardt before or [original lead singer] Steve Walsh. Well, I had started to play with Steve and then [guitarist/keyboardist] Kerry [Livgren] joined. “Can I Tell You” had been written and got us a record deal, but adding Kerry to the mix, he had so many songs already written, so we started to work on those, and twist ‘em, and turn ‘em, and it was just a very exciting time. For me and I’m sure for everyone else, I’ve never been in a band like this before. This is really something unique and special. From the first listen, I could tell that something was different about this bunch of guys. So we started working on material, and we headed into the studio and started recording. Our biggest dream was to actually record an album. That was the big time, to actually get with a record label, make an album and maybe get to tour it a little bit. We never dreamed anything beyond that…We had to wait quite a while for it because record companies have their slots when they’re releasing material. Hence, we kind of set up our own tour. We toured all over Kansas, played in all sorts of cities booking ourselves into different venues. Finally, the [“Kansas”] album came out and we were starting to get put on to some tours.

Our first gig, I think, was in Lincoln, Nebraska with The J. Geils Band. We had no idea what to do, so we’re kind of circling the building and we thought, “Well, I guess we’ll go around back.” So we’re talking to people, “Yeah, just load your gear here.” We didn’t know where to go or what to do and somebody directed us to a dressing room backstage. We went back there, and on one of the counters was a tray with like bread, bologna and cheese, and we froze. We just thought, “This has got to be J. Geils’ room. We’re in the wrong room!” So we walked out of there. “Oh no, that’s for you guys” (laughs). I mean we devoured the bologna tray and it was such a celebration. “We have finally made the big time. We’ve got our own dressing room and they gave us bread and bologna.” That’s how green and distant we were from success.

If that felt like the big time, what was it like when you guys actually started selling tickets and albums by the millions?

Williams: Well, it creeped in. We played a lot of shows where people had no idea who we were. We learned quickly. We got put on a show with Mott The Hoople and it was supposed to be Queen, but someone in Queen got hepatitis and they had to cancel at the last minute. We had just done a brief tour with Fleetwood Mac and a few other things, so they got us on this show with Mott The Hoople. There was no [social] media back then per se, and so nobody knew that Queen wasn’t [performing]. People were there to see Queen equally as much as Mott The Hoople. Kansas was nobody that they heard of. So the lights go out and, “Ladies and gentlemen, Kansas!” You could just hear this gasp and moan. “Where’s Queen?” So we come on stage and I will hear this on my deathbed, “Queen” (yells and laughs).

And we’re fresh out of the bars, so we learned quickly from that experience watching Mott The Hoople. It was a show. They’ve got a plan. They’re doing this song, this song, this song, this song. The lights are structured. There’s talking between songs once the show starts. We didn’t know how to do that kind of stuff, but we learned quickly from watching them and they kind of took us under their wing. We learned [to be] quick between songs. No tuning, no discussing, get on to the next tune. Don’t give them a chance to start yelling at you and just mow them over. We knew musically we could be accepted easily. Just don’t give them a break to start yelling at you (laughs), so that’s what we did. We just buried them in sound and we eventually would win them over every night. Hats off to Ian Hunter and Mott The Hoople for giving us professional rock and roll 101 lessons.

And we’re fresh out of the bars, so we learned quickly from that experience watching Mott The Hoople. It was a show. They’ve got a plan. They’re doing this song, this song, this song, this song. The lights are structured. There’s talking between songs once the show starts. We didn’t know how to do that kind of stuff, but we learned quickly from watching them and they kind of took us under their wing. We learned [to be] quick between songs. No tuning, no discussing, get on to the next tune. Don’t give them a chance to start yelling at you and just mow them over. We knew musically we could be accepted easily. Just don’t give them a break to start yelling at you (laughs), so that’s what we did. We just buried them in sound and we eventually would win them over every night. Hats off to Ian Hunter and Mott The Hoople for giving us professional rock and roll 101 lessons.

When did it feel like you finally arrived and how did you react?

Williams: The first album went okay. Now [record label founder Don] Kirshner wants a second album, [“Song For America”], so we went out to California and that was so much fun. I remember getting out of the studio at [midnight], one o’clock and getting back to the hotel. That’s about the time the hookers were starting to get off the streets, and they’re hanging around the hotel on the strip. Out behind the [hotel], they had a basketball goal. To unwind, we’d go back there and shoot hoops. We got to know some of the hookers and they started playing basketball with us (laughs). We’re from Kansas recording our second album for Don Kirshner and we just got off work. The hookers just got off work and they’re in their stiletto heels, sparkly clothes, short skirts and all their make-up, shooting hoops with us! It wasn’t a sexual thing. They were just unwinding too (laughs). I wish I had a movie of that or photos of us. I’m being guarded by some six-foot African American hooker as I’m trying to do a hook shot, but everything just seemed normal. We kind of understood, “We’re all getting off work and time to relax a bit.”

We did the first album in New York and the second album in Los Angeles. There was a lot of distractions, so we decided for the third album, [“Masque”], we needed to get somewhere where we can’t be bothered by the bright lights and the big city, and we found out about a studio back in Louisiana…We were still an opening act, but we’re building a following and we’ve got a good [response] with the college crowd and stuff. Then we did “Leftoverture” at the same place. “Leftoverture” exploded and that changed everything, but again, this had been like a three or four-year gradual process and you tend to take some things for granted after a while. The first one did pretty well, the next one did better, the next did much better. Then we’re gold and now we’re headlining, so I guess we’re too young and dumb to appreciate it at the moment, but all of a sudden, we’re playing Madison Square Garden, sold out, and our manager was so excited. We’re in the limo heading over from the hotel [and he said], “Oh, I can’t believe that we sold out Madison Square Garden” and we’re just kinda talking…

After the show, we were looking to go to Smiler’s Deli to get shrimp salad sandwiches. We were just not that affected by it. It just all came. The path had a direction and it was kind of a gradual one, so suddenly here we are. I don’t think it was really until years later that we had gratitude. I didn’t even know how to spell it back then, let alone what it meant or what it felt like, so now I can see it from a different perspective and appreciate all the steps along the way, and how great it was that album exploded. That was a career maker right there, but at the time, it wasn’t like, “We’ve made it.” It’s just, “Okay, we’ve been working hard and here we are. This is good. Keep your nose to the grindstone. We’ve got another album to make soon.” It was just always taking the next step forward, always working on what’s next, so we never really stopped to appreciate it at the time.

After the show, we were looking to go to Smiler’s Deli to get shrimp salad sandwiches. We were just not that affected by it. It just all came. The path had a direction and it was kind of a gradual one, so suddenly here we are. I don’t think it was really until years later that we had gratitude. I didn’t even know how to spell it back then, let alone what it meant or what it felt like, so now I can see it from a different perspective and appreciate all the steps along the way, and how great it was that album exploded. That was a career maker right there, but at the time, it wasn’t like, “We’ve made it.” It’s just, “Okay, we’ve been working hard and here we are. This is good. Keep your nose to the grindstone. We’ve got another album to make soon.” It was just always taking the next step forward, always working on what’s next, so we never really stopped to appreciate it at the time.

So many songs have since become classics. What do you account for the longevity of some from the 1970s in particular?

Williams: “Carry On Wayward Son” was the right time, the right place. It was not like any song. It had a lot of instrumental passages. It went from half time, to double time, to a lot of instrumental solos, just a lot of different things, but it was a really cool rock song. It wasn’t following the fad and fashion of the time so much, so it was unique, starting with a cappella. We weren’t the first ones to do it, but it was still a bit unique. It was a great lyric. Same with “Dust In The Wind.” There was nothing like that on the radio, except on an oldies station if you were listening to Peter, Paul & Mary or something. That definitely wasn’t following the fads of the moment, but it was just a solid song for every man. Lyrically, it was ambiguous, as was “Wayward Son,” so the common man, woman, could listen to that and relate to it from their own perspective. To me, that’s what makes a song timeless. It doesn’t date itself time-wise lyrically and it doesn’t date itself in a political sense or in a religious sense. It just is the common man’s struggles, or observations, or wondering. “What is this all about?” And to me, that creates the most interesting lyric. I struggle with any song that is instructing you on how it is. It leaves no room for interpretation, like that’s the problem I always had with music videos and MTV. Previous to that, you’d listen to an album, look at the cover, read the lyric sheets, look at the back. It was a whole experience that involved your imagination. Then with videos, it’s like, “No, no, watch this. This is what it is.” It kind of took all that away, so I’ve always gone for what makes you think, not so much as what makes you observe.

That brings up an interesting point because Kansas actually wound up having quite a run on MTV. Any thoughts?

Williams: I’m going to speak just for myself, for no one else in the band or anything, but in my opinion, I felt like a whore (laughs) and it was just done at gunpoint. We weren’t comfortable with it. We weren’t actors. It was humiliating. I didn’t enjoy it at all. [The television show] “Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert,” that was different cause that was bands performing live on stage. It was all shot at the Santa Monica Civic [Auditorium]. They brought in an audience and you played, and you better play it right because it’s not like you got to do it ten times in a row, so it was intimidating. [They] never stood there with a movie camera three feet from my face. It was terrifying, but we were a tight, well-rehearsed band, so what that fear created was tension and we kind of perform best [that way]. We’re not a soft jazz band. We play with a lot of tension and fear (laughs) and it creates an energy, like I’m just trying to keep up, as is everybody else, and the stuff we play is not that easy. I can’t go out, have a couple of beers and jump on the stage to do it. I’ve got to have all my wits about me, and so “Kirshner’s” was great because it really captured us trying to be calm. It looks calm while we’re playing it, but underneath we were all scared to death.

From simply the musical side, what are your feelings about the hits of the ‘80s?

From simply the musical side, what are your feelings about the hits of the ‘80s?

Williams: Glad they happened because they are a stepping stone [in] the millions of steps that have gotten us to where we are today. Today we’re having a blast after 50 years. We’ve got our foot in the door. It looks like I have a career, so now we can kind of relax with that aspect, like the record companies would want us to change. “We need another song because we don’t hear a hit” or whatever it was with whatever record company. Those were just things you did at gunpoint to stay with the company. But we always had our own personal integrity. Sometimes an outside song would come in. “You need to do this.” Well, we would twist it and turn it until we could make something palatable, something that had our stamp on it. Those weren’t my favorite things, but on the other hand, I understood the necessity of them. “We need to keep you on the radio. We need to keep you relative to the times,” all of that nonsense. I completely get it, but somewhere along the way, you feel a little dishonest in kind of bending to the business side of the music business.

How did you manage to navigate the many changes of the ‘90s?

Williams: The ‘90s was a weird time because classic rock was dead. It hadn’t made its return yet, but we still were a band. Now we’re riding around the country in a bus and buses are expensive. We’re not making much money. You’re playing five nights a week just to pay for the bus habit and I refer to it as the “dark ages.” I don’t remember much about it. I was probably drinking a bit too much. You would get off the bus, walk in the back door of a bar, walk in, play, get back on the bus, drive all night, wake up, walk in the backstage, or the back door of another bar, or small club, and that was ‘90s. There’s just not a lot about it, but I did learn a lot about us and about myself. We’re going to do this whether we’re playing Madison Square Garden or we’re playing in Thermopolis, Wyoming on a Tuesday for the grand opening of a bowling alley because we’re musicians. This is what we do and [we’re] always hopeful that things will get better, the next album something will happen, or the times will change, and we just rode it out.

Then classic rock started making a comeback. In 50 years, there’s going to be ups and downs, and more than once, probably more than ten times, but we’ve been riding a seven, eight, nine-year high. Things have just been going fantastic. I’m trying to think, “How do we follow this?” We’ve selected 50 cities, 50 dates, 50th anniversary, but it will continue beyond that next year. We’ll probably add, hopefully, another 30 shows to that. Then what? Give up? No, after that, probably start working on our new record and continue touring. I don’t know how to quit and I don’t know why I would. This is the best job in the world. I love being with the guys, the travel, the good times, the bad times, all of that is something I signed up for, something I was built to do. I’m a natural at being in a band.

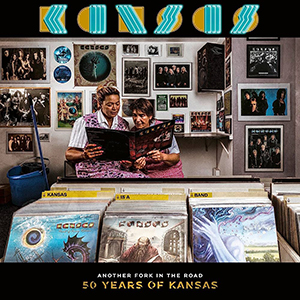

Tell us a bit about your selection process for the “Another Fork In The Road” collection and how it will factor into the show?

Tell us a bit about your selection process for the “Another Fork In The Road” collection and how it will factor into the show?

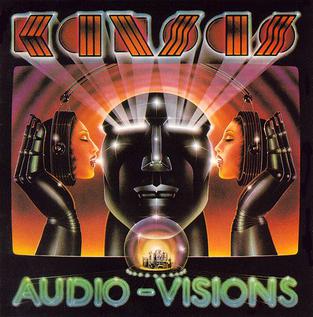

Williams: This was the first time that we ever let a record company make a decision. Inside Out and Thomas Waber are, foremost, big time Kansas fans and know our whole career, and they approached us. “Let us put this complication together from the fans’ perspective. It might not be something that you do” and honestly it wouldn’t have been. We would’ve kind of made another greatest hits album and it would’ve been similar to other things we had done, so we did kind of a hands off [approach]. Of course, with final approval we changed a couple of things, same with the album cover, so we had some to do with it, but pretty much the record company did.

Well, then the tour. We want to represent something off each album, each era, so that’s how we put the set list together. We’re playing a few songs that haven’t been touched in 45 years. It’s just really fun for me. I had to completely re-learn songs that I hadn’t played in that long, put on the headphones and try to find my part in it. That part was very reminiscent of being in a bar band before this band when you’re trying to learn cover songs (laughs) and you’re listening in the middle of the night with your headphones on to pick out guitar parts, to suddenly the new band is now performing them. Some of these were songs that we were working on when this band first got together and it’s reminding me of those moments. It’s very special when we start a song and the crowd has been screaming for it for 30, 40 years and now we’re playing it.

What comes to mind about coming to the Chicago Theatre and performing here in the past?

Williams: We’ve been to Chicago Theatre once, which is kind of like playing the Fox Theatre in Atlanta or playing the Fox in St. Louis. They’re iconic places to play. Finally, we got to play the Chicago Theatre [in 2018] and it was all that we hoped it would be. Now we get to go back, so that’s great, but we have such a history in this whole Chicago metro area. When we first went there, we were playing The Corporation, a little club out west of Chicago, and it was fantastic. [I have] just great memories of those times, playing the Aragon Ballroom with Hawkwind. We probably headlined there a few times or more and played there as an opening act three or four times. I remember it being a pretty rough area and we had security guards just to get into the building the first time. It was a great rock crowd. Playing Ravinia with the orchestra. I do remember some enormodome that we didn’t like to play cause it was just an echo dome. I don’t think that building exists anymore. Gosh, countless memories of playing Chicago. We have a lot of friends there. It’s always a lot of fun to come back and for Ronnie Platt being a hometown boy, I can’t imagine how excited he is to be going back to the Chicago Theatre cause that was a dream for him to play there one day…I’m very much looking forward to it. Chicago’s a great music town for us, always has been, always will be [and we] always will look forward to a Chicago show.

Kansas performs at the Chicago Theatre on Saturday, July 15. For additional details, visit

KansasBand.com, TheChicagoTheatre.com and LiveNation.com.