With “Every Breath You Take,” The Police’s Stewart Copeland will be watching the Genesee Theatre

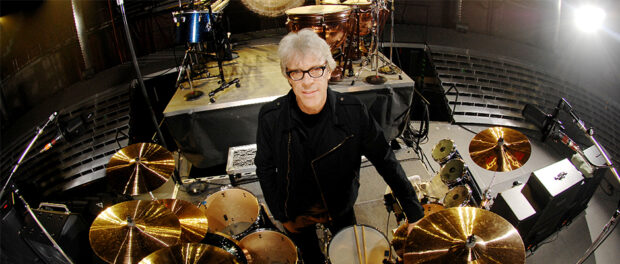

Photo provided by Rob Shanahan

Photo provided by Rob Shanahan

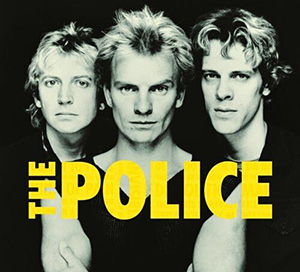

Rock and Roll Hall of Famers The Police barely spent a decade together as the English punk scene of the 1970s transitioned towards the new wave of the ‘80s, but thanks to the enormous “Every Breath You Take,” “Roxanne,” “Message In A Bottle” and what feels like a million more classics, the trio comprised of singer/bassist Sting, guitarist Andy Summers and drummer Stewart Copeland will likely last forever.

Outside of a one-off reunion from 2007-08 that sold out stadiums everywhere on earth, the creatively combative but behind the scenes friends pledged to never work together again, sending everyone back to solo life and simply socializing together.

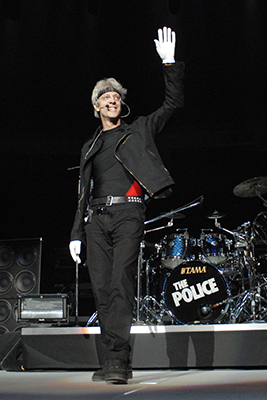

In the case of Copeland, who went on to score a plethora of films, TV shows, video games and even operas, plus find additional fame making jazzy pop with Animal Logic and jamming with Oysterhead, he’s back on the road with yet another ambitious project, “Police Deranged For Orchestra.”

The world-renown beat keeper rang Chicago Concert Reviews prior to performing at the Genesee Theatre in Waukegan on Friday, May 19, releasing a companion album on Friday, June 23 and preparing fall’s forthcoming book “Stewart Copeland’s Police Diaries,” sharing several witty and surprising antidotes about the band’s unlikely origins, breaking up at the top of its game and scratching other artistic itches throughout the surrounding side projects.

How long has this idea been brewing and where did the title of the show come from?

Stewart Copeland: Well, I’ve been playing shows with orchestra for decades. My 20 years as a film composer gave me an involuntary education in orchestra. During these shows where I play film scores and so on, I play a couple of the obscure Police songs that I wrote and they always go over so well, I thought, “How about I drop some hits in there?” Those go over really well and I was reminded that songs that have history have emotional power. Every band knows when they go the road with a new album, the new songs just don’t work as well as the old songs cause they’re new. Old songs have this power. Why with orchestra you might ask? Because that’s sort of where I was coming from when I started to look at this material.

Stewart Copeland: Well, I’ve been playing shows with orchestra for decades. My 20 years as a film composer gave me an involuntary education in orchestra. During these shows where I play film scores and so on, I play a couple of the obscure Police songs that I wrote and they always go over so well, I thought, “How about I drop some hits in there?” Those go over really well and I was reminded that songs that have history have emotional power. Every band knows when they go the road with a new album, the new songs just don’t work as well as the old songs cause they’re new. Old songs have this power. Why with orchestra you might ask? Because that’s sort of where I was coming from when I started to look at this material.

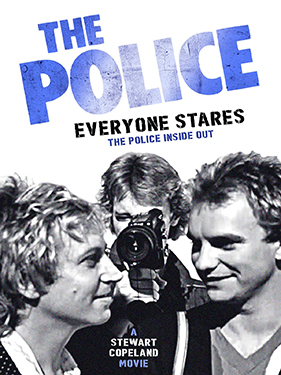

Why derangements? That is a different story and that’s the story of the Super 8 footage that I shot back in the day. I had a camera permanently glued to my eye for most of The Police experience, from the motels to Shea Stadium, but I couldn’t do anything with those films because they’re Super 8. There’s no negative and editing them is a pain, so they went into shoeboxes. One day, they invented computers whereby I could digitize those films, put them in a hard drive and play with them ‘til the cows come home, so I cut the home movie from hell about The Police ride, [“Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out”]. Well, Sundance invited me to show this home movie at the festival, which turned it into an actual movie for which I needed to create a score, and the score, obviously, could be Police music, but I didn’t want a couple things. First of all, The Police music is songs, not a film score. It’s not subservient to the plot twists of the story. It rages on. Also, I figured it would be good to have alternative Police, The Police that you haven’t heard, so I went into live recordings [and the] studio. I got all the multi-tracks from the albums, found other tracks of long lost guitar solos and vocalizations, and so on, and I created this alternative Police music, deranged Police music for the film.

Bring these stories together and we have “Police Deranged For Orchestra”…It does light up the building every time we play. It’s a different orchestra every night, but those songs have the baggage or history that makes it much more emotional.

For this particular show, what went into selecting the set list?

Copeland: The hits are the main thing cause they’ve got that power, but also just for the heck of it, I’ve gone into some obscure ones as well. I won’t tell you which ones. You can discover that on the night, but all your favorite hits. I think I’ve got ‘em all. I’m not sure what your particular favorites might be, but my particular hits and some more off-the-beaten tracks.

As you were going back through the group’s catalogue, did you discover anything you didn’t previously notice?

As you were going back through the group’s catalogue, did you discover anything you didn’t previously notice?

Copeland: Yes, I did. That they’re pretty damn good. Back in the day, I was at the back of the stage just banging s***. I had no idea what [Sting] was yelling about. I only saw the back of his head, so I discovered, and don’t ever tell him I said this, but Sting was a heck of a god**** songwriter. And those lyrics! I mean I appreciated the music, the chords, the harmony, the rhythms of what he wrote, but I never really appreciated the lyrics so much until I got in there and I had them in the score. I’ve got my three singers, my three soul sisters on the mic, and figuring out their harmonies and their parts, I had my nose rub deep in Sting’s lyrics and realized that the man’s a genius. The man is a genius and this orchestration is my revenge.

What were some of the ways The Police’s music was used that surprised you most?

Copeland: Sting’s favorite, and mine too, is that “Every Breath You Take” is played at weddings, and it’s a romance song, and people [say], “It’s our song.” In fact, it’s a twisted, sick perversion about a stalker and it’s fully evil in its intent. Nothing could make Sting happier than people misunderstanding his song. He’s a subversive f***** at heart.

How would you sum up the group’s evolution from its origins in the late 1970s into the ‘80s?

Copeland: In the late ‘70s, I formed a group, decided on the name Police, called that bass player I’d seen in New York, talked him into coming down to London, played him my songs and he joined the band. I’ve listened to these songs since. I’ve got all my tape recordings that I made back in the day. I’ve digitized them and they’re really crap. The miracle is that he didn’t run away when hearing these songs, which are basically bass lines with yelling designed for the punk world because there was no other world. The only way a band could get work was to be a punk band, fake or not, and we were just young enough so we could pass muster, although the London critics spotted us right away. So the evolution was from crap punk music written by me, to the joining of Andy Summers, who had all of this harmonic sophistication and guitar technique, and that unlocked Sting. The other miracle is that Andy joined us, not on the basis of hearing “Message In A Bottle,” or “Roxanne,” or “Every Breath You Take.” Sting hadn’t written any of those songs yet. Not even Sting knew he could do that. I think it was the distillation of punk music, where you reduce it to the bare essentials and take it from there. That was a good discipline for Sting, and when Andy joined with his much broader musicality, that unlocked the treasure chest of Sting’s songwriting and the rest is history.

By “Synchronicity,” you became the biggest band in the world. What was that like for you?

Copeland: Strangely unsettling. We were getting everything that every musician dreams of, but there was a sense of social vertigo that didn’t come overnight. We were acclimated gradually, but it still was not entirely comfortable to be on top of the world. For one thing, we were at each other’s throats and we’ve laughed about it since. We now understand that kind of tension was what made the band what it is, but at the time, The Police was not a comfortable place. I’ve described it as a Prada suit made out of barbed wire.

Copeland: Strangely unsettling. We were getting everything that every musician dreams of, but there was a sense of social vertigo that didn’t come overnight. We were acclimated gradually, but it still was not entirely comfortable to be on top of the world. For one thing, we were at each other’s throats and we’ve laughed about it since. We now understand that kind of tension was what made the band what it is, but at the time, The Police was not a comfortable place. I’ve described it as a Prada suit made out of barbed wire.

How was it to break up, basically at the top of the group’s game? Was this something you were able to walk away from peacefully?

Copeland: Absolutely. Our natural, inborn arrogance made it very easy to walk away. “I don’t need those guys.” It was only intended to be a temporary walk away just to recharge our batteries, but I got into film composing and never looked back.

How were you able to transition towards this second and very different chapter?

Copeland: I’ve always been a striver and I strove. I became a professional. I had been a rock star and I did discover that as a professional film composer, I could get rid of my snakeskin pants and be a normal human being. I turned myself back into a normal human, a suburban dad, driving my kids to school and going to Hollywood for work…I don’t score movies anymore. I was able to retire from that. I loved the work, loved the directors, loved everything. I wasn’t an artist during those years. I was a craftsman, an employee, and therefore derived great benefit from being forced to go places that I would not have gone as an artist. For instance, [it] never would’ve crossed my mind to get good at orchestra, except that it’s a main tool of scoring movies, so I delved into it and it became a lifelong passion. I never would’ve gone there had it not been for my stern boss, Francis [Ford] Coppola saying, “I need strings.”

It sounds like we have that period to thank for this point of your career.

Copeland: Very much so. Eventually, I did retire from that world. I couldn’t take the rat race of it, so I went where the marriage of music and story is most complete without the rat race and that’s opera. Now opera’s kind of a conversation stopper for many people, but I regard it as a theater with an orchestra in the pit, a team of talented singers and artists who just want to make great art and are not running scared from financial considerations. The business model is to lose money, so it’s a perfect world for the skills that I’ve picked up as a craftsman. I can now return to life as an artist in opera and it’s very rewarding. I’ve done seven operas now around the world. It’s just so much fun. I create the piece at home. I send it out there and I go out for a workshop early in their process…

How familiar was that community with your past? Was it mainly from film or The Police?

How familiar was that community with your past? Was it mainly from film or The Police?

Copeland: I thought at first that my rock star background would be alienating to that world. I couldn’t get away with pretending that my life was otherwise much, but one time in Italy, I did go to meet with an opera company. I had a suit, and a briefcase, and I was like Mr. Straight Arrow. Half way through the meeting, the guy was pretty much, “Dude, I know who you are. You play in a rock band.”

How do you look back on the unlikely reunion era of The Police during the 2000s?

Copeland: Very positively. It was a wonderful thing. It really punctuated the whole Police experience beautifully. We had forgotten about it, and when we talked about getting back together, it seemed like, “Yeah, this could be cool. Let’s fire it up. That’s fun.” We had no idea that stadiums around the world would sell out in 20 minutes. We had no idea the power of what the band had accomplished because it was only recently, and it didn’t occur to us that it also applied to The Police, but there was this thing that happened at the turn of the century when kids decided to rediscover the classics. Suddenly, Led Zeppelin, AC/DC are back and kids are turning onto Jimi Hendrix, and eventually, it turned out this reverence [applied towards] The Police as well. I never listened to my parents’ music, but kids these days do listen to their parents’ music and they can tell the difference between the knock-offs and the originals. We just thought The Police had faded. We made pop music to be consumed like a sandwich and forgotten the next day. We had no idea that the music had made such a deep impact that it would be remembered 30 years later.

Not only are fans coming back to the group, but other bands probably started because of The Police. Who are a few that have credited you as an influence?

Copeland: There’s a demographic bandwidth of bands – Primus, Foo Fighters, Tool, Rage Against The Machine – that age group are all kind of their late ‘40s and ‘50s now. In fact, Tool is in their ‘60s, but they were 16 back in the day, so when I go among them, they strew rose petals before me and bow down as if I’m a f****** Beatle or something. It’s great company (laughs). I guess most famously the Foo Fighters just because Dave Grohl and Taylor [Hawkins] made being fan boy-ing cool again. What do I mean, it was never cool, but they made it cool to be fan boys, so now everybody openly worshippers their forbearers in music and it’s a wonderful thing to be one of those forbearers.

What’s your relationship with your bandmates these days?

Copeland: Very good. Andy and I live in the same city. We see each other occasionally. There’s various things that we talk about. Police releases, new box sets and stuff that keep us in touch. Sting-O, we cross paths occasionally, get along very well, just don’t mention music (laughs). We can talk about music, [but] let’s not make music because we drive each other insane. The tension that created The Police, there’s still tension and his idea of what music idea is for is very different from my idea of what music is for. Let’s just stay friends and not pick up our instruments.

Do they have any thoughts on this show?

Do they have any thoughts on this show?

Copeland: Sting’s gonna come out one of these nights. I mean he loves it. It makes him feel like Rodgers and Hammerstein to have people doing his songs. I’ve always regarded songs as just something for the band to play. He writes songs to create something that exists and that has its own life, and when other people perform it, that kind of validates what he put into that song, so he’s all supportive. I sent him a huge tome of the concert scores, conductor’s scores of the pieces and can imagine him going cross-eyed trying to read it.

What’s your take on switching from stadium to theatre mode?

Copeland: Stadium life these days is more like Oysterhead, which is not quite Dodger Stadium, but the last Oysterhead show we played for 20,000 people. That is very exciting and very rock and roll. We’re a jam band, so we just make the s*** up on the night and we play rarely, so it’s always fresh. The concert experience is very different in these beautiful theatres, just the atmosphere of the theatres, the resonance of the stage, playing with orchestras. I’ve now bonded with them. At first, I was intimidated [by] these strange musicians who could only read music and can’t improvise, but now as a composer [I can relate]…Every detail I put on the page, they will faithfully execute it, unlike my favorite guitarist, who I’ll show him what the deal is and he’ll say, “Okay, I got ya.” Then he takes it and turns it into his own thing, and rock musicians, or as I call them, musicians of the ear, they don’t connect with music with their eyes on the score. They stare off into space and connect with their ear, improvising. The orchestra doesn’t improvise. They play what is on the page. If I put it there, they’ll play it. If I don’t put it there, they won’t play it and I love them for that.

What type of itch does Oysterhead scratch that you can’t with other projects?

Copeland:The improvisation part is very cool. I myself improvise a lot during the “Deranged” shows because the orchestra is so exact that I can take a left whenever I want to and “I’ll meet you at the double bar line.” I can go wherever I want cause I know exactly where they will be. However, I do not know where [Phish’s] Trey [Anastasio] and [Primus’] Les [Claypool] are gonna be [in Oysterhead], so we stick together, listening to each other. We interact, we throw each other stuff, it comes back at us, we deal with it and take it to a new place. The interaction is a three-way interaction rather than I’m doing my thing while the orchestra’s right there. It’s three guys feeding each other stuff and running with stuff. It’s a very different artistic experience, and by the way, the two things compliment beautifully. They refresh each other.

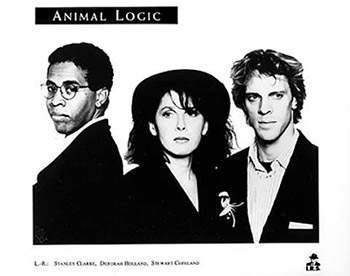

Going back even further, where did Animal Logic fit into the equation?

Copeland: Way back in the day, [jazz bassist] Stanley Clarke and I decided, “We’re such hot shot musicians, let’s get a real songwriter, [Deborah Holland], and make some pop music, put some art into it.” So we did. It was called Animal Logic and we had a nice run with that. Stanley and I have been playing with each other for decades…Some of my best friends are jazz players. I once did a tour of Europe playing all the jazz festivals and I discovered whatever I might think of jazz musicians, the jazz audience is one of the most beautiful things, in the same way that jam band audience is a beautiful thing. In jazz, you don’t need to be subservient to the song. F*** the song. There is no song. Audiences there want to see your chops, all of them all the time. There’s no such thing as holding back, so playing for a jazz audience is one of the most fulfilling experiences, even though since my daddy raised me to play jazz, I usually don’t.

Copeland: Way back in the day, [jazz bassist] Stanley Clarke and I decided, “We’re such hot shot musicians, let’s get a real songwriter, [Deborah Holland], and make some pop music, put some art into it.” So we did. It was called Animal Logic and we had a nice run with that. Stanley and I have been playing with each other for decades…Some of my best friends are jazz players. I once did a tour of Europe playing all the jazz festivals and I discovered whatever I might think of jazz musicians, the jazz audience is one of the most beautiful things, in the same way that jam band audience is a beautiful thing. In jazz, you don’t need to be subservient to the song. F*** the song. There is no song. Audiences there want to see your chops, all of them all the time. There’s no such thing as holding back, so playing for a jazz audience is one of the most fulfilling experiences, even though since my daddy raised me to play jazz, I usually don’t.

You’ve come to Illinois a lot throughout all of these different artistic outlets. What stands out when you think of coming to town?

Copeland: My daughter graduated from Northwestern [University], that’s one. But also, the Aragon Ballroom. We played there a million times. [The Rosemont Horizon] was kind of funky, but the audience always rocked it. It was kind of an old, crusty, dusty arena, sort of like The Forum used to be before they buttered it up, but it had a vibe. It’s probably been renamed three times since we’ve been there.

We’ve played [Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field]. I’ve discovered that baseball teams are really into porn. The bathrooms of the dressing rooms of Wrigley field are stacked with pornography. Wrigley Field is cool because you’re playing and there’s the audience in the stadium, and [as] you look [outward], all the neighboring buildings have bleachers and stands. It’s sort of like the concert extends into the city, literally. They got a ticket to their neighbor’s apartment rooftop, [but] as long as they’re singing along, I don’t mind!

Stewart Copeland performs at the Genesee Theatre on Friday, May 19. For additional details, visit StewartCopeland.net and GeneseeTheatre.com.